On the afternoon of 27 May, BritCham Shanghai Legal & Regulatory Committee co-hosted with the Singapore Chamber of Commerce (SingCham) for a session focusing on the extraterritorial impacts of EU climate and environmental laws on companies exceeding specific turnover thresholds within the EU or those engaged in EU-related supply chains.

Prof. Adolf Peter, Co-Chair of the Legal and Compliance Committee of the British Chamber of Commerce Shanghai underlined that the Council and the European Parliament had just adopted the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The CSDDD would enter into force on the twentieth day after being published in the Official Journal of the European Union. Next to the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the CSDDD would be the most comprehensive and strictest ESG/environmental/climate-related statutory law worldwide. The two directives will directly bind large companies inside and outside the EU. Small and medium-sized companies will be indirectly impacted by having to comply with ESG-related contractual obligations imposed by the companies within the direct scope of the ESG-related EU law and contractually cascaded throughout the supply/value chain.

Arbitration is a swift and fast dispute resolution mechanism for environment and climate change disputes. Hosting this event, China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) has been actively promoting arbitration exchange between China and Europe through its office in Vienna while expanding its service to global commercial entities.

Prof. Adolf Peter provided drastic examples from practice for environmental/climate related disputes involving multinationals such as BMW, RWE, Shell, Eni and TotalEnergies. He outlined the massive direct and indirect impact of the CSDDD and the CSRD (including the topical climate change standard ESRS E1 which obliges reporting entities to report their Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions if they are material) on companies, including Chinese entities, involved in EU-related supply chains. Prof. Peter reiterated that environmental/climate-related obligations would have to be passed on throughout supply/value chains by means of contractual cascading giving rise to substantial damage claims and removing violating supply/value chain members as a last resort. He also pointed out the immense significance of supply/value chain-related indirect upstream and downstream Scope 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions which are by far the largest part of companies’ total GHG emissions in many sectors. Finally, Prof. Peter predicted that climate-related contractual clauses setting clear, quantified (e.g. mandatory year-on-year decarbonisation rates to achieve net-zero) and verifiable targets as well as containing liquidated damages provisions would become common in the near future. The CSRD/ESRS allows companies with net-zero targets to only use carbon credits and offsets for their residual emissions.

Weina suggested four reasons for choose arbitration to resolve disputes related to sustainability and environment. Firstly, confidentiality can be better ensured via arbitration than litigation. Secondly, enforceability is higher for arbitration compared to litigation which faces cross-jurisdictional problems. Thirdly, the flexibile nature of arbitration allows new arbitral rules to be introduced to resolve disputes involving multiple contracts and multiple parties. Fourthly, arbitration is a more efficient process as it generally lets the dispute crystallise as soon as possible so that downstream contracts can be determined.

Tracy shared that there is going to be an increase in the number greenwashing claims and claims against companies who are unable to fulfil their contractual obligations. She affirmed that arbitration is an effective dispute resolution mechnism because of the flexibility of procedure and how parties are able to appoint their arbitrator. She also highlighted that lawyers and law firms are not spared from the risk of facing ESG claims as law firms are considered a supplier of legal advice and therefore involved in the companies’ operations.

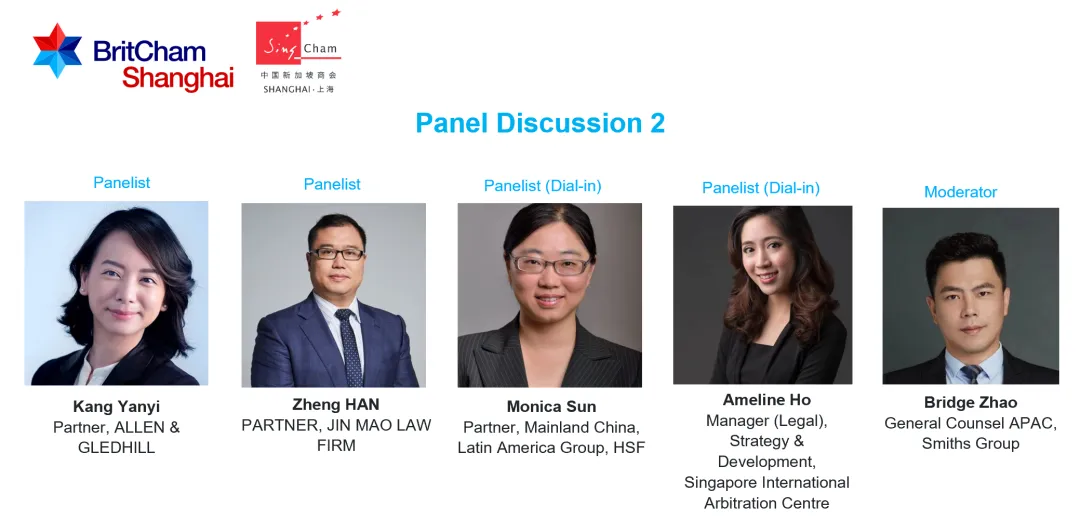

Zheng Han raised potential issues that will arise during arbitration proceedings due to the highly technical and complicated nature of ESG disputes, such as whether it is the tribunal’s responsibility to fill the gap if the parties do not have mutual understanding about their obligations. He also stressed the need for experts in such disputes which potentially costs more for the parties involved in addition to challenges on finding the appropriate expert and properly using the expert’s reports to support their claims. Furthermore, he highlighted that sometimes liability can be difficult to determine due to poor performance of the facility that led to failure to meet contractual obligations.

Coming from a corporate perspective, Monica presented on how the nature and content of due diligence is going to change for companies in transactional context. While traditional due diligence focuses on legal ownership of assets, contractual rights and legal proceedings, ESG due diligence can involve looking at the companies’ ESG risk exposures arising from their polices and systems. There can be several different approaches to ESG due dilligence: system testing, ‘triaging’,principles-based diligence and full due diligence, each with their pros and cons in terms of scope of coverage and time and cost effectiveness.

Ameline pointed out that the nature of disputes legal professionals see are a reflection of industry and business trends and therefore, a rise in the number of ESG disputes reflects how the industry is ever more concerned about ESG issues. The subject matter of disputes that the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) has seen include areas relating to construction, supply agreements, regulatory standards and breaches of exclusive distribution agreements. These disputes usually involve contractual disputes over construction, non performance or failure to meet quality standards and cases arising from production problems due to nature-related interference. The cases SIAC has seen spans different jurisdictions, with 90% of its caseload being international in nature.

Yanyi added that although most ESG, especially climate change cases, currently opt for litigation, arbitration is increasingly a preferable alternative due to its confidentiality, enforceability and flexibility. She highlights three types of disputes that corporations should look out for. Firstly, director duties’ disputes, currently seen with NGOs seeking to hold major corporations accountable for their failure to take active and consistent steps towards achieving their net-zero commitments. Secondly, greenwashing disputes, for example in the form of government enforcement actions against corporations’ ESG claims. Thirdly, supply chain disputes, for example, holding corporations accountable for their failure to address human rights risks or deforestation violations in supply chain, which are commonly overlooked.

This event enabled vibrant discussions among panellists from diverse backgrounds and engaged audiences. The panellists also shared their insights and experiences regarding the topic with the audience. The BritCham Shanghai extend our gratitude to the SingCham for co-hosting this event with us.